33. Besotted with Beefcake: A MichelangelHO Story

/In this episode of History is Gay Leigh and guest host Amanda Helton discuss Michelangelo Buonarroti. THE Michelangelo. And we'll get into all the juicy deets you didn't learn in art history class, full of stories of broken noses, the gay art of forgery, big ol’ artist egos, and attempts to answer the question, “what even is a titty”?

But first, let me introduce to you our guest host for this episode, Amanda Helton!

Amanda Helton is a fine arts professional working in Silicon Valley, focusing on digital strategy and museum technology. She is originally from Sevier County, Tennessee (birthplace of Dolly Parton), and HAS MET HER a few times! Amanda holds a Masters Degree in Art History (with a concentration in Museum Training) from the George Washington University in Washington, DC. She is passionate about connecting the history of art and technology to the present day. Amanda is a sunscreen evangelist, friend to every dog, and co-runs a Xena re-watch group with Leigh!

You can find more from Amanda on Instagram at @oryxbesia and at www.amandahelton.com!

A Closer Look at Michelangelo…

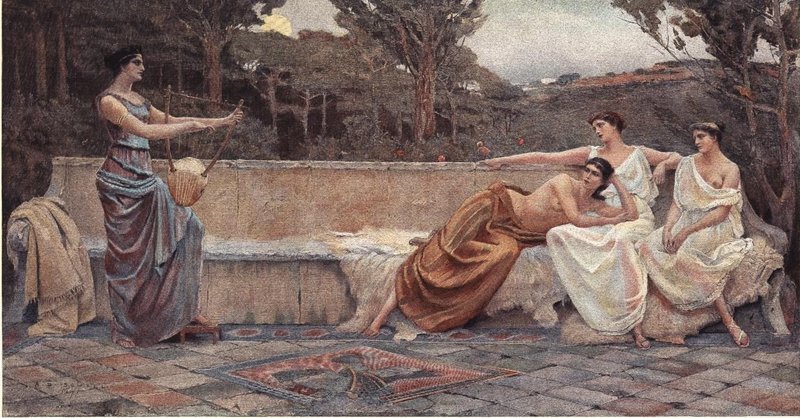

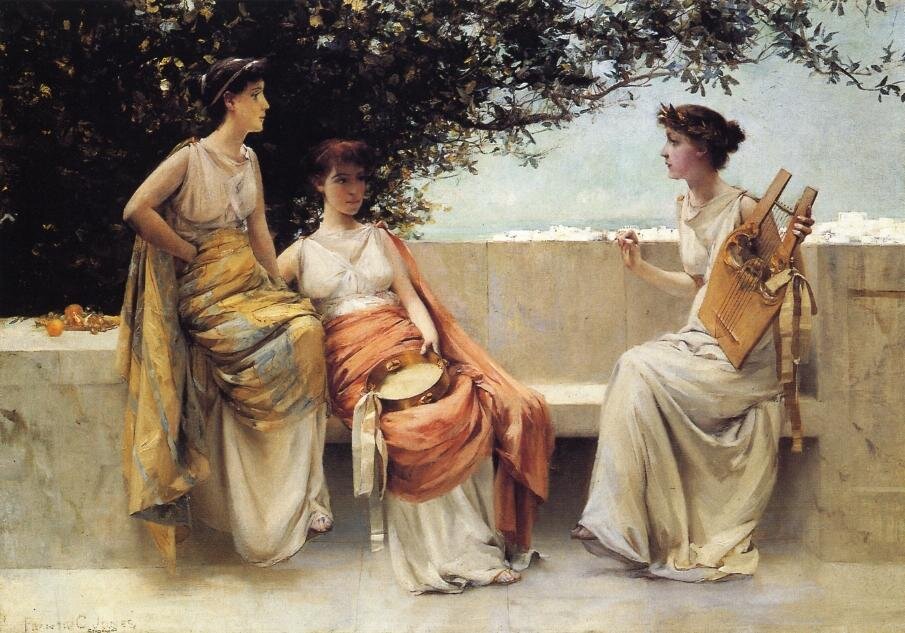

First, a little bit of background on what art in this period was like! Although the ancient Greeks and the Romans understood how to create an image with convincing depth, frescoes from the Villa of P. Fannius Synistor clearly show the use of perspectival systems; during the middle ages, art changed to reflect the church. No longer were artists pursuing realism.

Villa of P. Fannius Synistor, ca. 50–40 B.C., Fresco, (Boscoreale, Italy)

Brunelleschi observed that parallel lines appear to converge at a single point in the distance with a single fixed point of view and discovered a method for calculating depth used by painters, sculptors, and architects alike to lend greater realism to their work. One of the first paintings during the Renaissance to fully implement perspective is Holy Trinity by Masaccio. Here, you can see the impression of a false room has been created on a flat wall. The coffers on the ceiling make the orthogonal lines, and the vanishing point is at the base of the cross, which happens to be at the viewer's eye level. This creates the illusion that the space the viewer is looking at is a physical continuation of the space in which they are standing.

Masaccio, Holy Trinity, c. 1427, Fresco, 667 x 317 cm, (Santa Maria Novella, Florence, Italy)

Here’s some other art we discussed in the episode:

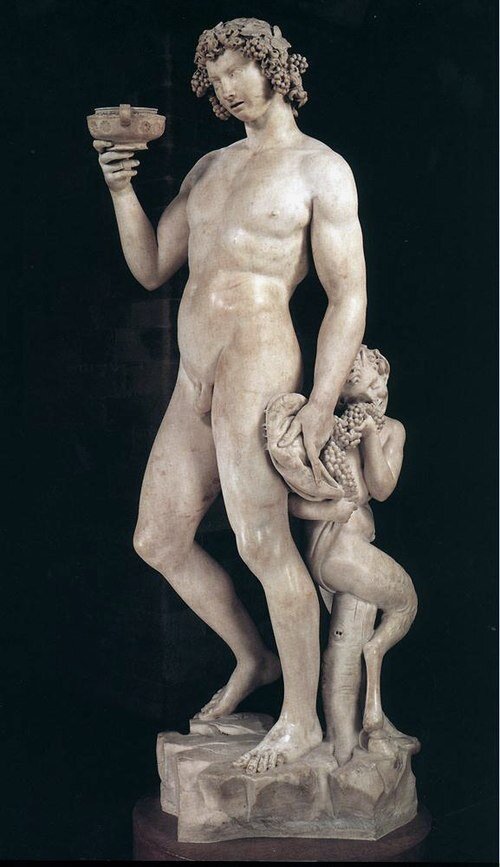

Cardinal Riario commissioned a statue of Bacchus, the Greek god of wine and celebrations. However, the Cardinal didn't like it because Bacchus looked too drunk, LOL, and refused to pay for the work.

Michelangelo, Bacchus. Museo del Bargello, Florence, Italy.

The David commission was started by two other sculptors who failed and left the marble in an almost unusable condition. In 1501, when Michelangelo took the job, it was impossible to portray David with Goliath's head at his feet (as was traditional) because of the marble's damage. So, he depicted David in the moments before the battle instead. He worked on this project for three years, and it was an incredible success.

Michelangelo, David, 1501-1504, (Florence, Galleria dell'Accademia)

Michelangelo, Moses, 1505-1545, Tomb for Julius II, ( San Pietro in Vincoli (Rome)

Michelangelo’s Moses has horns due to a longstanding tradition of antisemitism in which Jewish people were portrayed as “horned devils administering to Satan.”

Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel paintings abound with moments that make you go, WTF is happening here? They attest certainly at least to his awareness of various sexualities. In Last Judgment, on the wall behind the altar and to the left of Christ, are the damned destined for Hell. Among them are two pairs of nearly nude and quite muscular fellows in a lip-locking embrace in addition to an older bearded man staring longingly into the eyes of a younger man.

Michelangelo, Last Judgment, 1534-1541, Sistine Chapel, altar wall, fresco, (Vatican City, Rome)

The poet Pietro Aretino accused Michelangelo of “desecrating the Sistine Chapel by turning it into a whorehouse with his naked figures.”

Detail from Last Judgment

Detail from Last Judgment

Detail from The Last Judgment. Don’t piss off Michelangelo or he might make a snake bite your penis in the underworld and give you donkey ears

If you’d like to see what The Last Judgment looked like prior to Danny the Panty Painter’s censoring, you can check out a copy of it done by Marcello Venusti, one of Michelangelo’s apprentices. This is the best approximation of what the fresco looked like before the addition of loincloths and underwear throughout the following years from its completion.

Pietá, C. 1498-1499, Marble, michelangelo

In the Florentine Pietá sculpture he made later in life, he included a self-portrait representing himself as a Nicodemist. The Nicodemists, active in Italy in the 1540s and early 1550s, showed interest in some of the Protestant reformers' ideas but sought to act within the existing Catholic order, thus preventing schism in the Church. This self-portrayal reinforces existing evidence of Michelangelo's involvement with the Catholic Evangelist Reform movement in Italy.

The Deposition (also called the Florentine Pietá, Bandini Pietà or The Lamentation over the Dead Christ), c. 1547–1555, marble, left unfinished and partially destroyed by Michelangelo, restored by Tiberio Calgagni, (Museo dell'Opera del Duomo, Florence)

Detail of The Deposition

In the Renaissance, androgyny was ideal for men and women. Mario Equicola, a Renaissance humanist, wrote in 1525 that ‘the effeminate male and the manly female are graceful in almost every aspect’ – a view commonly held by his peers. There are many examples of iconic androgynous figures in Renaissance art. Take Donatello’s David, who stands leaning, leg forward, with a hand on his hip and a soft, round little belly. Michelangelo’s intense and hyper-idealized androgyny in his Sistine Chapel frescoes may be a reason why his peers found the work so influential.

Donatello, the bronze David, ca 1440, (Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence, Italy)

Marble tomb of Giuliano de' Medici by Michelangelo, 1520–34; in the Medici Chapel, San Lorenzo, Florence.

What even is a titty?

Michelangelo’s presentation drawings for Tommaso Cavalieri:

The Punishment of Tityus, Presentation Drawing by Michelangelo

In the myth, the giant Tityus was punished for attempting to rape Lato, Apollo and Diana's mother, by being chained to a rock in Hades. Every day a vulture would rip out his liver, the seat of lust; every night, the liver would grow back, for the torment to be repeated the next day, for all eternity. The drawing could be interpreted as a representation of pining and a love that will never be realized. Since the liver is continuously pecked out only to grow back again for all of eternity and the liver is often referred to as the "seat of the passions," the scene could refer to Michelangelo's unrequited love for Cavalieri.

The Rape of Ganymede, Presentation Drawing by Michelangelo

Ganymede was a cupbearer for Zeus. Zeus fell into such lust for the young cupbearer that he took on the form of an eagle to sweep Ganymede off to Mount Olympus to be with him. Ganymede could represent the young Cavalieri, and the eagle could represent the mature and overpowering Michelangelo, making it a visual representation of Michelangelo's physical desire for Cavalieri.

Many scholars suggest that the figures in Michelangelo’s Victory statue in the tomb of Julius II are modeled on Cavalieri (the standing figure) and Michelangelo (kneeling). It’s hard to miss this statue's obviously erotic elements, depicting Michelangelo between Cavalieri’s legs.

The Genius of Victory (1532–1534), marble, (Palazzo Vecchio, Florence)

If you want to learn more about Michelangelo, check out our full list of sources and further reading below!

Online Articles:

Books and Print Articles:

Francese, Joseph. "On Homoerotic Tension in Michelangelo's Poetry." MLN 117, no. 1 (2002): 17-47.

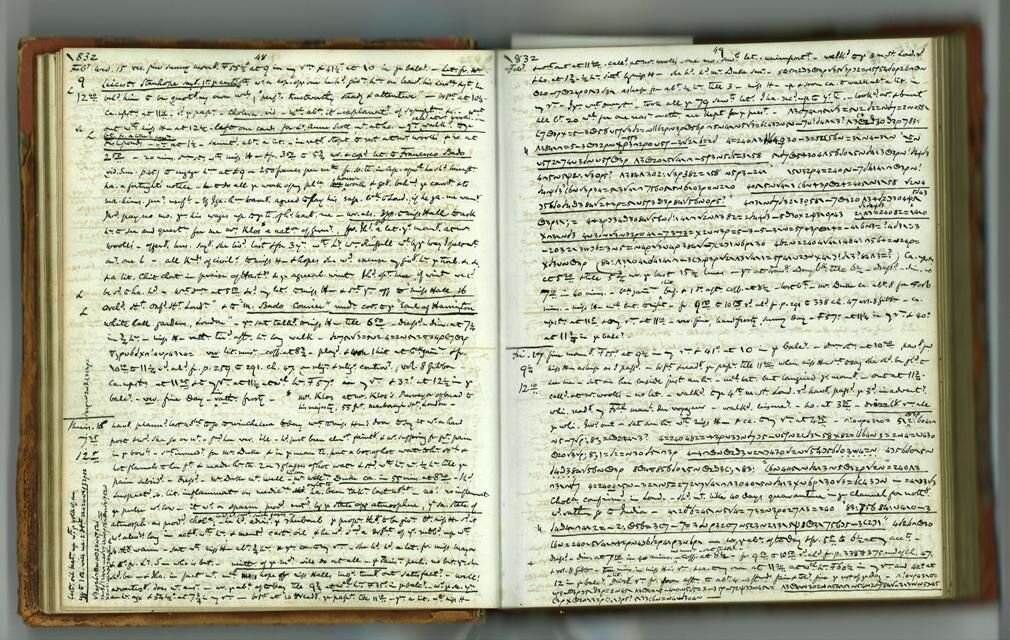

The Sonnets of Michelangelo, 1904 Edition

Shrimplin, Valerie. "Hell in Michelangelo's "Last Judgment"." Artibus Et Historiae 15, no. 30 (1994): 83-107.

Renaissance Humanism, from the Middle Ages to Modern Times by John Monfasani

Summers, Claude J. "Homosexuality and Renaissance Literature, or the Anxieties of Anachronism." South Central Review 9, no. 1 (1992): 2-23. Accessed November 21, 2020. doi:10.2307/3189384.

Gender and Society in Renaissance Italy

Baskins, Cristelle L. "GENDER TROUBLE IN ITALIAN RENAISSANCE ART HISTORY: TWO CASE STUDIES." Studies in Iconography 16 (1994): 1-36. Accessed November 21, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23924090.

Schwarz, Arturo. "Alchemy, Androgyny and Visual Artists." Leonardo 13, no. 1 (1980): 57-62. Accessed November 21, 2020. doi:10.2307/1577928.

Friedrichsmeyer, Sara. "The Subversive Androgyne." Women in German Yearbook 3 (1987): 63-75. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20688686.

Eckstein, Bob. The History of the Snowman. United Kingdom: Gallery Books, 2007.

Trollope, T. Adolphus. "Michelangelo and the Buonnarroti Archives." The North American Review 125, no. 259 (1877): 499-516.

Parker, Deborah. "The Role of Letters in Biographies of Michelangelo." Renaissance Quarterly 58, no. 1 (2005): 91-126.

Love Sonnets and Madrigals to Tommaso De'Cavalieri by Michelangelo Buonarroti

Public Domain Poems by Michelangelo

Barolsky, Paul. "MICHELANGELO'S EROTIC INVESTMENT." Source: Notes in the History of Art 11, no. 2 (1992): 32-34. Accessed November 21, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23203048.

Goldberg, Jonathan. Queering the Renaissance

Smithers, Tamara. 2016. Michelangelo in the New Millennium: Conversations about Artistic Practice, Patronage and Christianity. Boston: Brill. p. vii. ISBN 978-90-04-31362-0.

Gayford, Martin (2013). Michelangelo: His Epic Life. London: Penguin UK. ISBN 978-1905490547.

Chris Ryan, The Poetry of Michelangelo: An Introduction, Continuum International Publishing Group Ltd., 97–99.

Vittoria Colonna. Sonnets for Michelangelo. Ed. Abigail Brundin. Chicago: Chicago University Press, 2005.

Howard Hibbard, Michelangelo

J. de Tolnay, The Youth of Michelangelo, p.11

Gardner’s Art Through the Ages

Italian Renaissance Art, Laurie Schneider Adams

Alberti’s Perspective: A New Discovery and a New Evaluation, Samuel Y. Edgerton Jr.

Bertman, Stephen. "The Antisemitic Origin of Michelangelo's Horned Moses." Shofar 27, no. 4 (2009): 95-106. Accessed October 18, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42944790.