46. A Husband is Unnecessary: Yoshiya Nobuko & Japanese Girls' Culture

/This episode has EVERYTHING: gay haircuts, yearning, rage against the patriarchy, they were *roommates*....let’s talk about the magical world of Yoshiya Nobuko, girls’ culture, and lesbian fiction in Taishō era Japan!

Leigh is joined by guest host Erica Friedman, speaker, editor, researcher and an expert on all things Yuri. Yoshiya Nobuko was an extremely popular writer in 20th century Japan who lived with her beloved female partner for 50 years and her legacy continues today as “the Grandmother of Yuri.”. The tropes and storylines established in her writing can still be seen today in queer girls stories in and outside of Japan– get ready to learn all about modern Japan’s very own Sappho. After all, it’s all in the yearning.

Erica Friedman (she/her) holds a Masters Degree in Library Science and a B.A. in Comparative Literature, and is a full-time researcher for a Fortune 100 company.

She has lectured at events around the world and presented at film festivals, notably the San Francisco Lesbian and Gay Film Festival and the London Lesbian and Gay Film Festival. She has participated in an academic lecture series at MIT, University of Illinois, Harvard University, Kanagawa University, and others.

Erica has written about Yuri for Japanese literary journal Eureka, Animerica magazine, the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund, Dark Horse, Del Rey and contributed to Forbes, Slate, Huffington Post, Hooded Utilitarian, Anime News Network and The Mary Sue online. She has written news and event reports, interviews Yuri creators and reviews Yuri anime, manga and related media on her blog Okazu since 2002.

She is the author of a cyberpunk novella and is the author of By Your Side: The First 100 years of Yuri Anime and Manga, published by Journey Press.

Locate Erica upon the internet:

A Closer Look at Yoshiya Nobuko

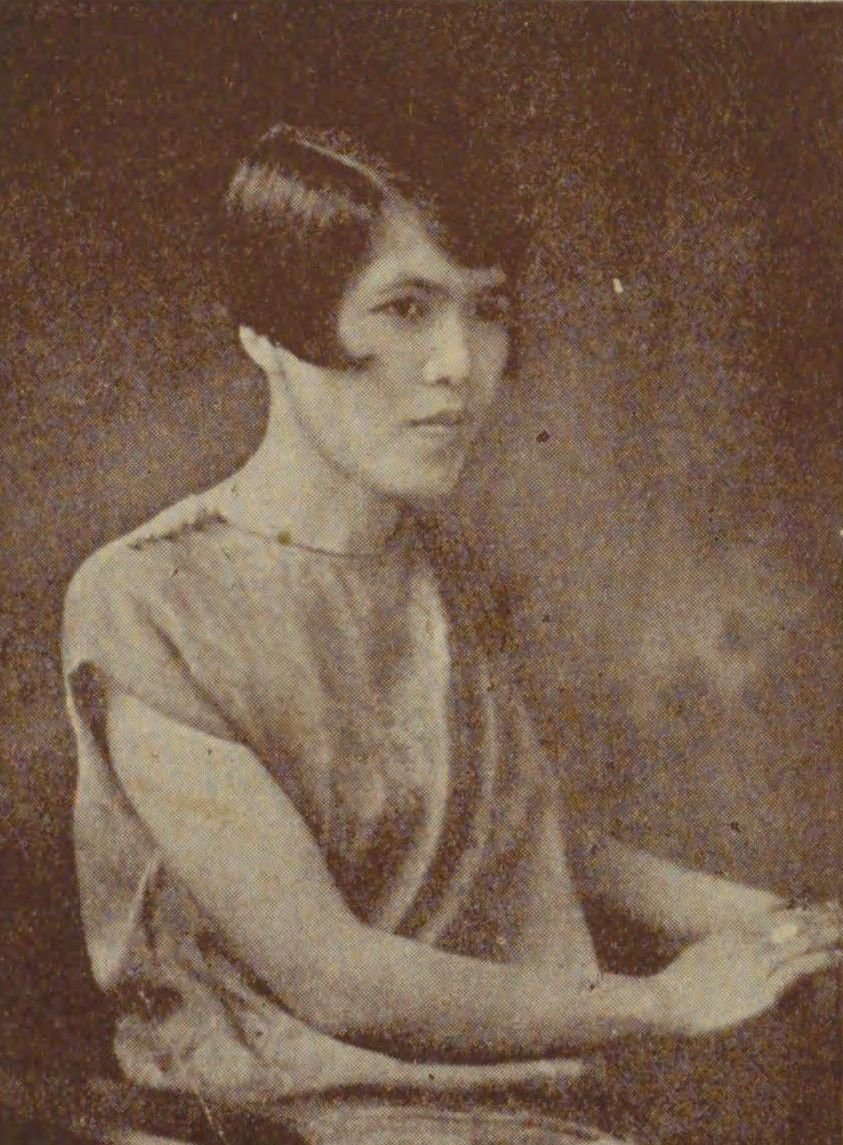

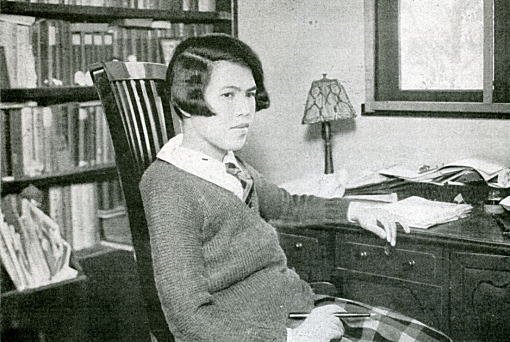

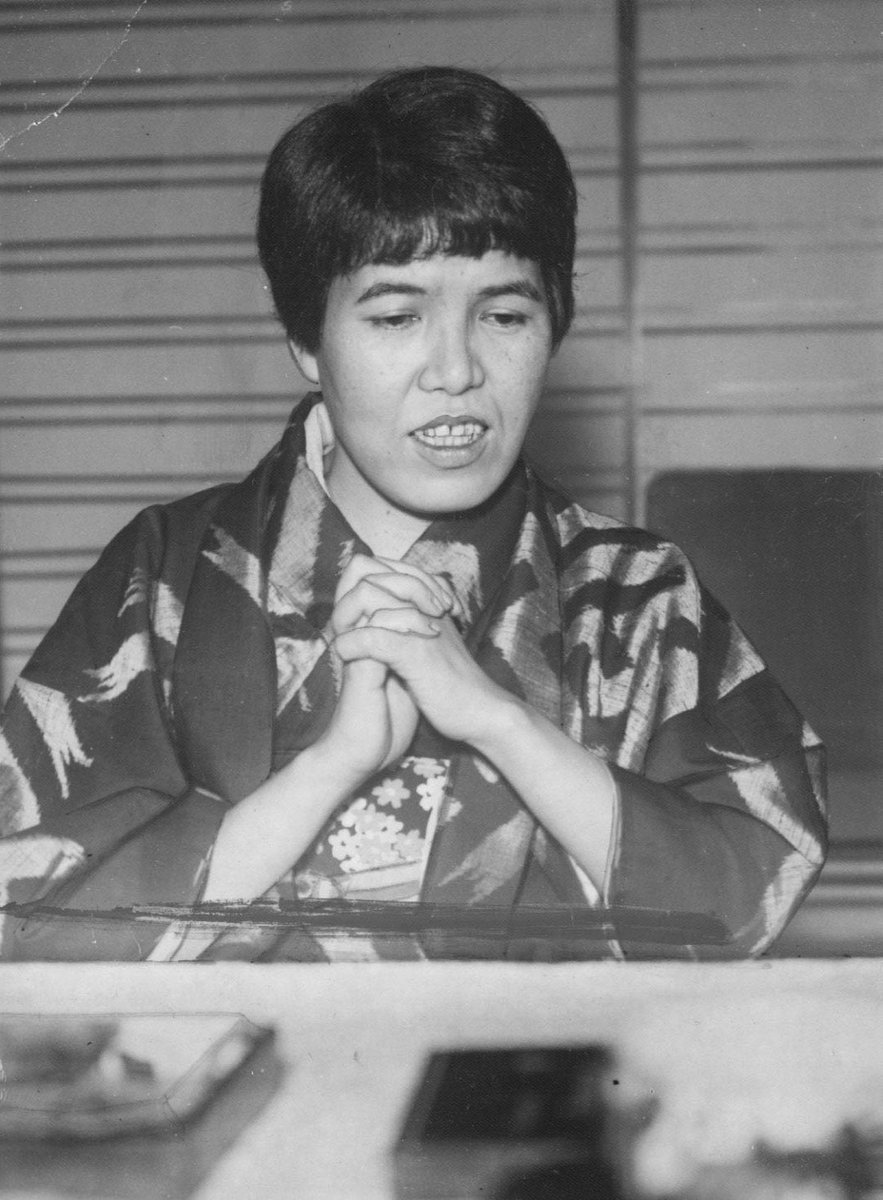

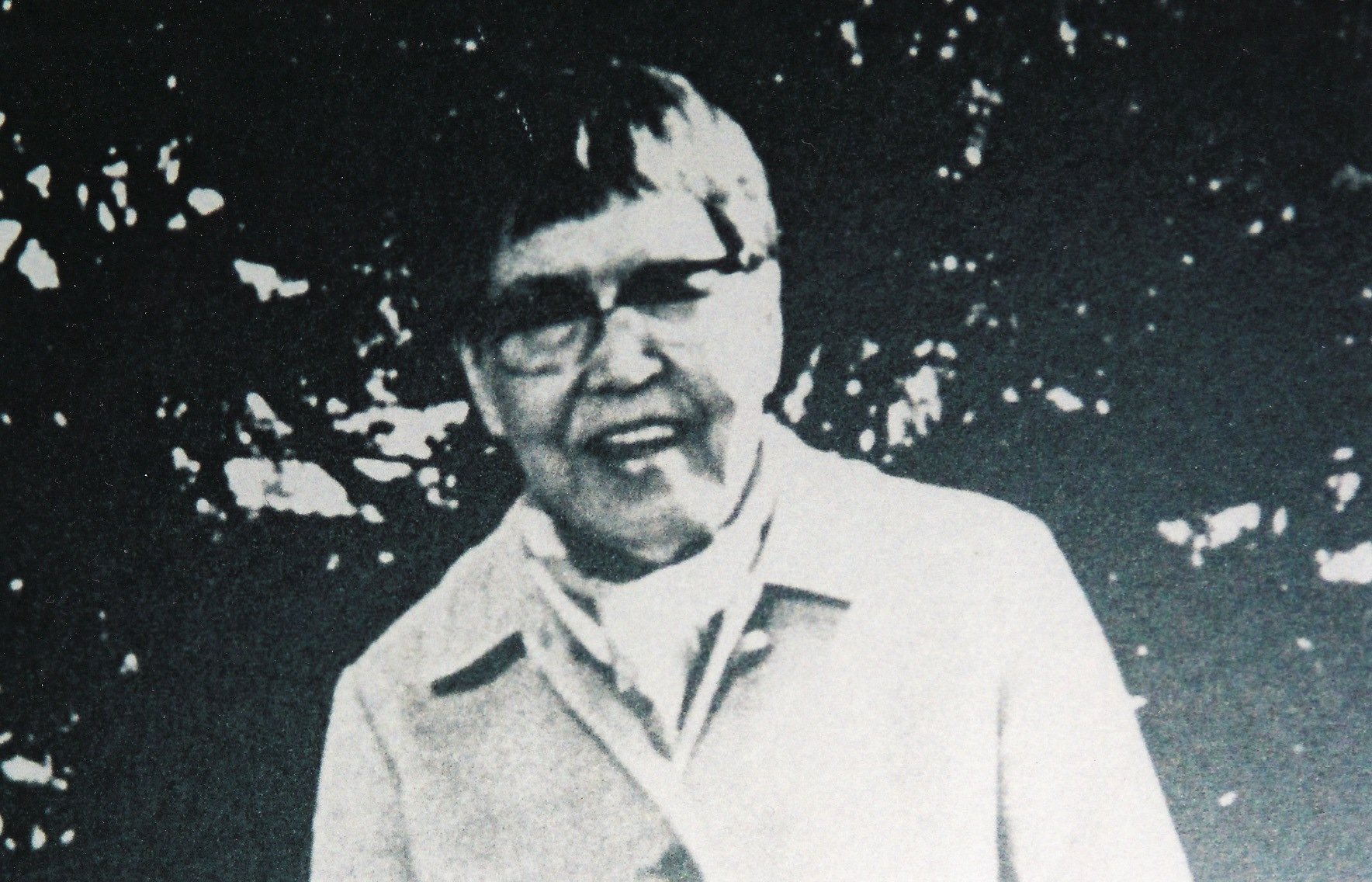

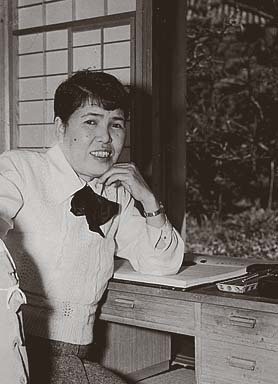

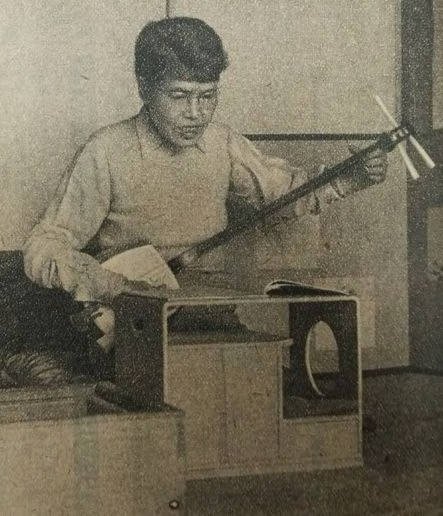

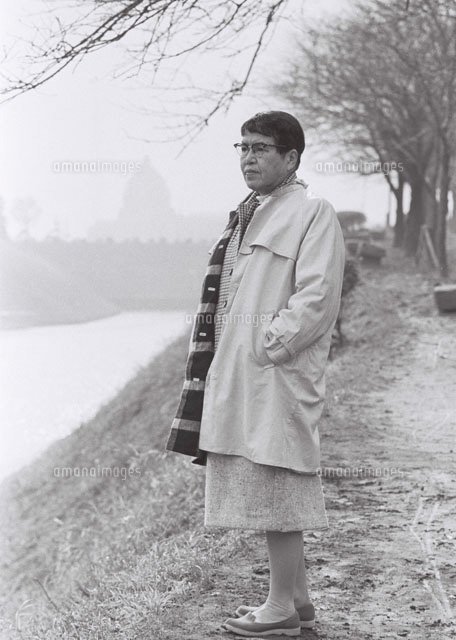

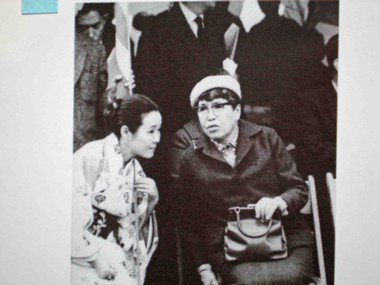

We’ve gathered some photos of Yoshiya (and friends) throughout her life for you to check out here!

Young Yoshiya

Yoshiya and Monma Chiyo: Wife for Life!

Yoshiya and Monma fell in deep love the moment they met, and their letters to each other reveal so much about their dynamic, we had to share them here!

Yoshiya to Monma, 1923:

Beloved Chiyo

I will love you no matter what

I do not wish to make you lonely

Nor do I want to be lonely

I want you to be the source of my strength

And, if you will let me, I would like to be the source of your strength

May 23, 8:30 pm

Arriving home soaking wet from the rain

Nobuko

Monma to Yoshiya, 1923 (she addresses Yoshiya as onesama, or "older sister," a popular euphemism then and now for one half of a lesbian couple)

Beloved elder sister. I am unspeakably lonely when you leave. My heart becomes hollow, and all I am able to do is to sit in a chair and stare blankly at the wall. It’s now nighttime, isn’t it? As I wrap my unlined black kimono around my bare skin and adjust the hem, my body is aroused by feelings of longing [for you]; instead, what stretches confusingly before my eyes is dusty reality. Ah, this evening. My heart finds no consolation in this evening dream of mine or in reality. My heart sinks from a heavy sadness. If only on this night we were together in our own little house, lying quietly under the light of a lantern, then my heart would gradually warm and neither would you be so sad. I am so sad that I won’t be able to see you either tomorrow or the day after. Let us please meet again on Tuesday. Farewell for now; I am forever yours. Why have I written such things, I wonder? Please don’t worry too much about me. Goodbye, and please take care of yourself.

May 11, midnight

Thinking of my elder sister.

Chiyoko

Monma to Yoshiya, February 1925:

I can only think of how soon we can arrange to live together. There’s nothing I need more than your warm embrace. It is unfortunate that we are not a male and female couple, for if you were a male, our union would be quickly arranged. But a female couple is not allowed. Why is it that [in our society] love is acknowledged only by its outward form and not by its depth of quality — especially since there are so many foul and undesirable aspects to heterosexual relationships?

And Yoshya’s response:

Chiyo-chan. After reading your letter I resolved to build a small house for the two of us…Once it is constructed, I will declare it to be a branch household (bunke), initiate a household register [listing, by law, all family members], and become a totally independent household. I will then adopt you so that you can become a legal member of my household (adoption being a formality since the law will not recognize you as a wife. In the meantime, I aim to get the law reformed). We will have our own house and our own household register. That’s what I’ve decided…We’ll celebrate your adoption with a party just like the typical marriage reception — it will be our wedding ceremony. I want it to be really grand. We will ask Miyake Yasuko-san and Shigeri-san [the couple who had introduced them] to be our go-betweens. I wonder what kind of wedding kimono would look best on you?

Yoshiya in WWII, part of the Pen Butai propaganda corps

Yoshiya Nobuko’s work is not without criticism, and we must mention that during the second world war, she was part of a journalistic propaganda unit of the Japanese government called the pen butai, a group of writers who traveled through areas occupied under Japan’s imperial campaign and control, including China, Manchuria, Indonesia, Thailand, Vietnam, and others, writing dispatches published in Japanese newspapers. There are very few photos, but we were able to find a few.

Yoshiya with Kan Kikuchi, Eiji Yoshikawa, and others being welcomed at tokyo station

Yoshiya with Kan kikuchi and others outside of a plane in manchuria, during her time in the pen butai

Older, Delightfully Butch Distinguished Yoshiya

Shojo Bunka and the covers of Yoshiya’s works

Yoshiya was writing at a time when girls’ magazines were hugely popular and instrumental in turning shojo bunka into an entire subculture. Here’s some covers of some popular shojo magazines and Yoshiya’s works!

On the left, a 1908 issue of Shōjo sekai (少女世界, "Girls′ World"), one of the first girls’ magazines in japan. On the right, a cover of sarah frederick’s translated version of “Yellow Rose”, one of the stories in Yoshiya’s hana monogatari (花物語 "Flower Tales")

cover of hana monogatari (花物語 "Flower Tales")

Cover of “Two Virgins/Two Maidens in the attic”, yaneura no nishojo, 1919

Yoshiya Nobuko Memorial Museum

Yoshiya and Monma’s house in Kamakura was turned into a museum after Yoshiya’s death, containing memorabilia from her life and preserving her study and living spaces. It’s open twice a year.

And lastly, check out Erica’s conversation with Sarah Frederick all about Yoshiya for Yuricon!

If you want to learn more, check out our full list of sources and further reading below!

Online Articles & Resources:

Books and Print Articles:

Coutts, Angela. “Gender and Literary Production in Modern Japan: The Role of Female‐Run Journals in Promoting Writing by Women during the Interwar Years.” Signs, vol. 32, no. 1, 2006, pp. 167–95.

Dollase, Hiromi Tsuchiya. “Yoshiya Nobuko’s ‘Yaneura No Nishojo’: In Search of Literary Possibilities in ‘Shōjo’ Narratives.” U.S.-Japan Women’s Journal. English Supplement, no. 20/21, 2001, pp. 151–78.

Dollase, Hiromi Tsuchiya. “Mad Girls in the Attic: Louisa May Alcott, Yoshiya Nobuko and the Development of Shōjō Culture.” Purdue University, 2003.

Dollase, Hiromi Tsuchiya. “Early Twentieth Century Japanese Girls’ Magazine Stories: Examining Shōjō Voice in Hanamonogatari (Flower Tales).” Journal of Popular Culture, vol. 36, issue 4., 2003, p. 724-755

Fanasca, Marta. “Tales of lilies and girls’ love. The depiction of female/female relationships in yuri manga.” Tracing Pathways 雲路. Interdisciplinary Studies on Modern and Contemporary East Asia, 2020, pp. 51-66.

Frederick, Sarah. Turning Pages: Reading and Writing Women’s Magazines in Interwar Japan. University of Hawai’i Press, Honolulu, 2006.

Frederick, Sarah. “Not That Innocent: Yoshiya Nobuko’s Good Girls.” Bad Girls of Japan, 2005.

Frederick, Sarah. “Sisters and Lovers: Women Magazine Readers and Sexuality in Yoshiya Nobuko’s Romance Fiction.” Love and Sexuality in Japanese Literature, PMAJLS, vol. 5, Summer 1999

Frederick, Sarah. “Women of the Setting Sun and Men from the Moon: Yoshiya Nobuko’s ‘Ataka Family’ as Postwar Romance.” U.S.-Japan Women’s Journal. English Supplement, no. 23, 2002, pp. 10–38

Fujimoto Yukari, and Translated by Lucy Fraser. “Where Is My Place in the World? Early Shōjo Manga Portrayals of Lesbianism.” Mechademia, vol. 9, 2014, pp. 25–42

Kan, Satoko, et al. “The Destinations of ‘Women’s Friendships’: Imperializing Education in ‘The Women’s Classroom.’” U.S.-Japan Women’s Journal, no. 43, 2012, pp. 106–25.

Matsugu, Miho. “Fight to Win: Female Bonding and War Propaganda in Yoshiya Nobuko’s ‘The Woman’s Classroom’, 1939.” U.S.-Japan Women’s Journal, no. 35, 2008, pp. 54–79.

Pflugfelder, Gregory M. “‘S’ is for Sister: Schoolgirl Intimacy and ‘Same-Sex Love’ in Early Twentieth-Century Japan.” Gendering Modern Japanese History, edited by Barbara Molony and Kathleen Uno, 2005.

Robertson, Jennifer. “Dying to Tell: Sexuality and Suicide in Imperial Japan.” Signs, vol. 25, no. 1, 1999, pp. 1–35

Robertson, Jennifer. “The Politics of Androgyny in Japan: Sexuality and Subversion in the Theater and Beyond.” American Ethnologist, vol. 19, no. 3, 1992, pp. 419–42.

Robertson, Jennifer. “Theatrical Resistance, Theatres of Restraint: The Takarazuka Revue and the ‘State Theatre’ Movement in Japan.” Anthropological Quarterly, vol. 64, no. 4, 1991, pp. 165–77.

Robertson, Jennifer. "Yoshiya Nobuko: Out and Outspoken in Practice and Prose," The Human Tradition in Modern Japan. (Ed.) Ann Walthall. Wilmington, DE: Scholarly Resources, 2002; 155-174.

Shaffer, Julia (2016) "Liberation Through a Different Kind of Love: Same Sex Relationships in the New Woman’s Movement," Historical Perspectives: Santa Clara University Undergraduate Journal of History, Series II: Vol. 21 , Article 9.

Summerhawk Barbara and Kimberly Hughes. Sparkling Rain: And Other Fiction from Japan of Women Who Love Women. New Victoria 2008.

Suzuki, Michiko. “Writing Same-Sex Love: Sexology and Literary Representation in Yoshiya Nobuko’s Early Fiction.” The Journal of Asian Studies, vol. 65, no. 3, 2006, pp. 575–99.

Videos